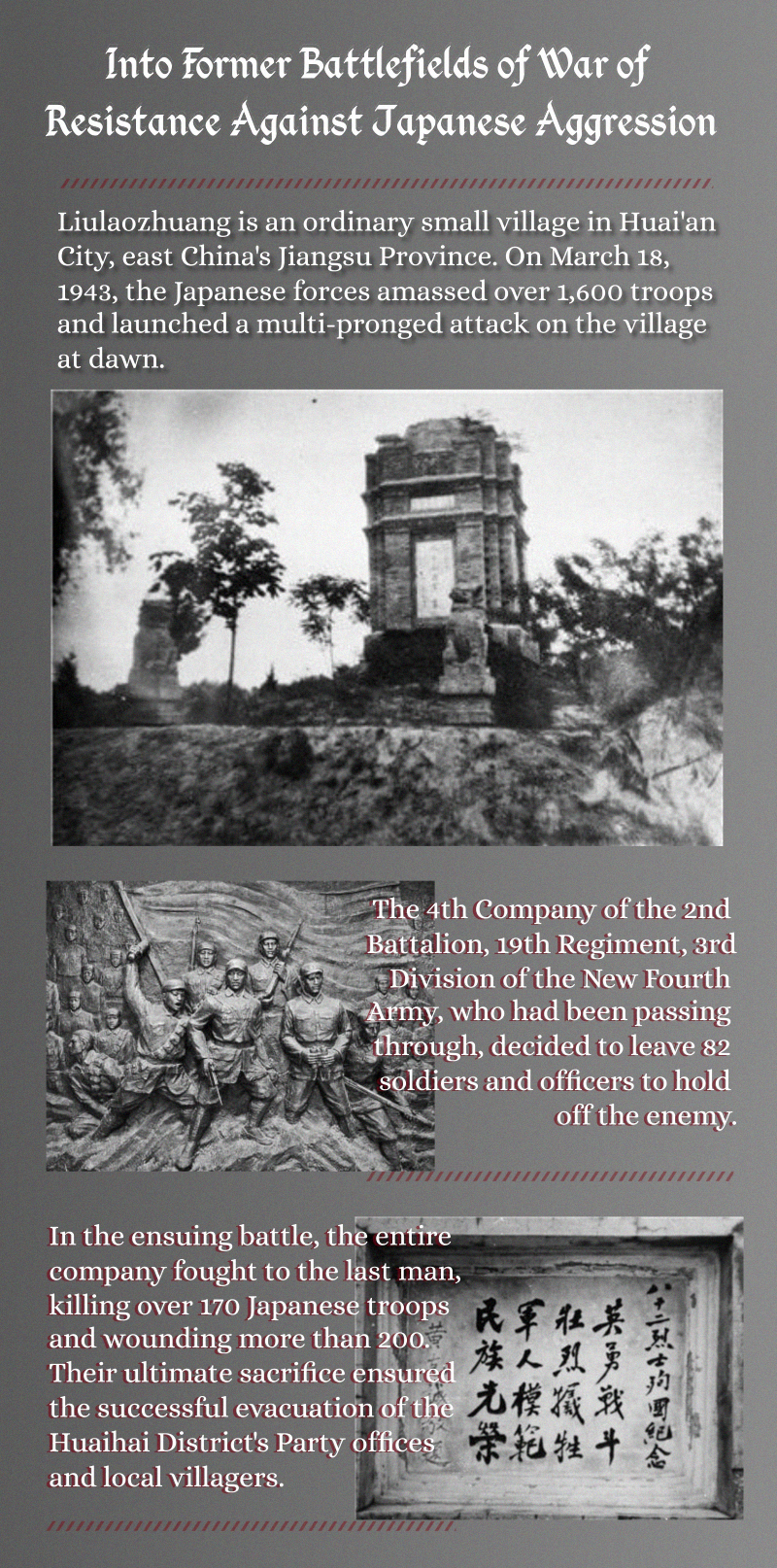

March 18, 1943. Under a sky heavy with clouds and a dense fog, dawn was late in coming to Liulaozhuang.

In the dim morning light, Japanese bayonets glinted through the mist. Enemy soldiers were barely 300 meters from the village’s entrance.

“Contact!” Bai Sicai, commander of the Fourth Company, 2nd Battalion of the New Fourth Army, sprang to his feet and dashed out of the village with a pistol in his hand, shouting, “Fourth Company! Get ready for combat!”

Sporadic gunshots rang out. Villagers quickly moved to the rear of the village, and in moments, the Fourth Company had assembled at the front.

Through the lingering mist, the blurred outline of the enemy flag emerged.

A messenger ran to Bai Sicai with the order: “Fourth Company, hold the southern line! Cover the battalion headquarters and the Sixth Company as they withdraw northeast. Hold for ten minutes, then disengage, and follow up immediately!”

Joining the Red Army at 16, Bai had already seen countless brutal battles at the age of 24. Since the counter-mopping-up campaigns began, such skirmishes had become commonplace. Ten minutes was not a difficult task for him and the Fourth Company.

By that time, the Japs had flooded into the village. Fanning into skirmish lines, they were charged with a murderous intent.

In an instant, the heavy machine guns of the Fourth Company roared. The first wave of Japanese soldiers fell.

But soon, more surged forward again.

The Fourth Company was engaging the 54th Infantry Regiment of Japan’s 17th Division. During the massive Spring Mopping-Up Campaign in Northern Jiangsu in 1943, the 17th Division employed “iron-walled encirclement” and “combing” tactics. They mobilized over 3,000 infantry and more than 500 cavalry, determined for a decisive battle with China’s main forces, aiming to obliterate the Yanfu (Yancheng-Funing) Base of ours and turn Northern Jiangsu into a “secure” rear base for their invasion.

The Maxim heavy machine guns of the Fourth Company roared, and Japanese soldiers fell, wave after wave. Seizing this interval, the Fourth Company swiftly withdrew from the fight.

Northern Jiangsu’s flat plains offered no natural defenses. Local Party branches therefore dug a four-foot-wide, five-foot-deep communication trench between villages—leveraging existing ditches and streams—to evacuate civilians and move covertly under Japanese patrols.

The Fourth Company retreated northward through the trench. But soon, frenzied Japs closed in from all sides.

Unfortunately, the trench ended abruptly—the massive roots of an ancient tree blocked the channel.

Several soldiers attempted to leap out of the trench and break through, but they were immediately met with a storm of fire from the enemy. In the distance, Japanese cavalry units were already circling.

Bai remained calm. He scanned his surroundings: the mist had completely disappeared, the fields were clear as far as the eye could see, and distant village houses with mud walls and thatched roofs were now sharply visible.

“My village, my people — to lay down my life for you would be a noble sacrifice,” Bai Sicai vowed to himself.

Political Instructor Li Yunpeng rallied the men: “We are the New Fourth Army! Heroes of our nation! We carry the Red Army’s legacy! The Japs are our sworn enemy—we’ll fight to the end!”

Eighty-two warriors shouted back: “Fight!”

After the brief exchange of fire at the village entrance, the Japs had roughly gauged their opponent’s strength: perhaps a hundred to eighty men, with only a few heavy machine guns. They believed the battle would be over in two or three assaults at most, so they ordered the infantry to launch a fight, without even unloading their mountain guns from the horses.

As the enemy closed to within 50 meters of the trench, Fourth Company unleashed its full firepower, hurling grenades like a torrential downpour. Japanese soldiers and their horses were thrown into chaos.

Another wave surged forward, only to be met with a volley of bullets. The enemy dropped and crawled in panic. Before the 200-meter-long trench lay dozens of enemy corpses, some no more than a few steps from the edge.

“Commander! Ammo’s low!” one soldier reported. “Commander! I’m out!” cried another.

Since the Counter-“Mopping-up” campaign began, the Fourth Company had been fighting bitterly for days without any resupply. Bai looked at the enemy corpses outside the trench—each one was laden with full ammunition pouches.

“I’ll go!” Platoon Leader Wei Qingzhong crawled out of the trench, leading several soldiers as they crept toward the enemy corpses. The Japanese clearly spotted their intent and concentrated their gunfire on them. Wei fell in a pool of blood, yet he managed to push the scavenged ammunition into the trench.

As infantry charges failed, the Japanese wheeled out mortars and grenade launchers to pound the trench. Bai and Li were wounded; many perished in the barrage.

When Bai regained his consciousness, most of his comrades had sacrificed. The few who remained were still firing stubbornly at the advancing enemy.

Another Japanese charge was repelled!

The Japanese couldn’t fathom it: the Chinese soldiers were outgunned, outnumbered, entrenched in dirt—they should have no chance after firing the first shot. But how come these men refuse to yield even an inch?

The Japs had no idea that the “Iron Fourth Company” they were dealing with was the backbone of the 19th Regiment, 7th Brigade, Third Division of the New Fourth Army. During the Northern Expedition, this unit, originating from “Ye Ting’s Independent Regiment,” had stormed Wuchang; during the Long March, they were the ones who bravely seized Luding Bridge and fought bloody battles at Lazikou; at Pingxing Pass, they had struck terror into the hearts of Japanese invaders... Hu Bingyun, commander of the 19th Regiment, once proudly declared: “Each of my soldiers is worth ten of my enemy’s!”

The sun began to dip toward the west. The Japanese assaults showed no signs of letting up.

Political Instructor Li Yunpeng convened the final Party branch meeting of the day. Young soldiers, one after another, applied to join the Party on the battlefield: “I will dedicate my life to the Party and the people, and I will never shame the Party or the nation!”

Bai then gave the order: “Burn all documents! Dismantle the light and heavy machine guns! Remove the parts from the rifles! Leave no complete weapon for the enemy and give them no trophies to boast about!”

The Japs launched yet another artillery barrage, turning over almost every inch of land. Before the smoke had cleared, Japanese cavalry and infantry charged together. Crawling out from thick dirt, Bai issued his final command: “Fourth Company, fix bayonets!”

The mere twenty-odd remaining soldiers, holding shattered rifles and brandishing bent bayonets, charged towards the Japs amidst the blood-red setting sun.

Marshal Chen Yi wrote in “The New Fourth Army in Central China”: “By 5 p.m., all had perished. The entire Fourth Company died with honor — including Company Commander Bai Sicai, Deputy Commander Shi Xuefu, Political Instructor Li Yunpeng, Cultural and Educational Officer Sun Zunming, Platoon Leaders Wei Qingzhong, Jiang Yuanlian, Liu Dengfu, and a total of 82 men below them—no survivors, and no surrenders.”

On the 50th anniversary of the martyrs’ sacrifice, General Hu Bingyun penned an essay titled “Mourning Old Comrades”, in which he wrote: “Long after the battle ended, the enemy finally, with trembling hearts, entered the trenches. They took no living prisoners, seized no intact weapons. Their only spoils were the more than 170 dead bodies and over 200 wounded soldiers, of their own, that they carried back.”

In 1946, Li Yimang, then Chairman of the Jiangsu-Anhui Border Region Government, composed a couplet for the Liulaozhuang 82 Martyrs’ Cemetery: “From Shaanxi to Northern Jiangsu, their heroic name as Eighth Route Army echoed behind enemy lines; from dawn till dusk, the entire company fought bitterly and perished at Liuzhuang.”

Three days after the Battle of Liulaozhuang, Peng Mingzhi, commander of the New Fourth Army’s Seventh Brigade, made a decision at Zhengtankou Primary School in Lianshui: to rebuild the Fourth Company and name it the “Liulaozhuang Company.”

From then on, the Liulaozhuang Company fought across China, achieving remarkable feats. They annihilated Japanese invaders, fought in Western Liaoning, captured Beiping and Tianjin, pacified the Huaihai region, crossed the Yangtze River, and finally liberated Hainan Island, becoming a proud banner of the People’s Army. On a similar early spring morning in Jianghuai, we arrived in Liulaozhuang. Across the fields, bright golden rapeseed flowers were in full bloom. The warm sun glowed softly, a gentle breeze whispered, and the shoulder-high rapeseed flowers swayed in the wind, stretching endlessly into the distance, merging seamlessly with the whitewashed walls and dark-tiled roofs in the background.

This peaceful and serene spring day was utterly captivating!

Unnoticed, the sun had already begun to set in the west. The elementary school nearby had dismissed for the day, and children were joyfully bouncing and shouting as they ran out of the campus.

An old man, carrying a floral-patterned schoolbag, walked towards us, holding his young grandson’s hand. We overheard the old man kindly tell his grandson, “Time to go home, time for dinner. Braised eel... Pingqiao tofu...”

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享