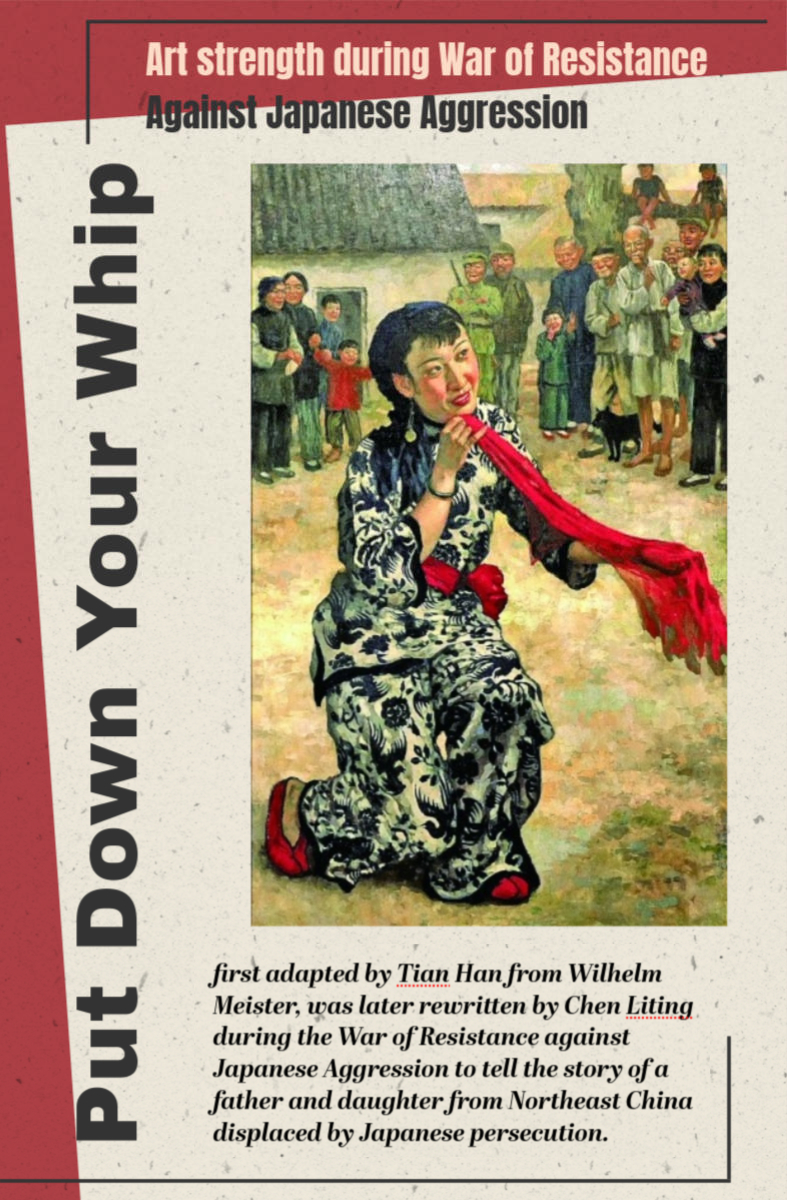

An oil painting by Xu Beihong once set a new auction record for Chinese oil paintings in 2007, selling for 71.28 million yuan. Its title: Put Down Your Whip.

Turning back to 1939: While holding an exhibition in Singapore to raise funds for the War of Resistance, Xu Beihong encountered the New China Drama Troupe, which was performing there. After watching star actors Jin Shan and Wang Ying in the street play Put Down Your Whip, Xu was deeply moved. In about ten days, he completed the oil painting. Writer Yu Dafu praised it, remarking that “the painting clearly shows a drama unfolding, with a sea of people watching Xiangniang.” In the flames of war, Put Down Your Whip not only inspired countless patriots to join the resistance but also created two artistic classics—one in drama, one in painting—becoming a landmark example of cross-genre artistic transformation.

The street play Put Down Your Whip spread widely, with many versions. Its origins trace back to playwright Tian Han. In December 1928, inspired by a fragment of Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister, Tian wrote a one-act play titled Muniang. It told the story of a Gypsy father forcing his sick daughter to perform, even raising his whip against her—until the young Wilhelm Meister intervenes to save her. With its simple characters, clear structure, lyrical narration, and sharp conflict, the short play resonated powerfully with audiences.

In the summer of 1931, director Chen Liting, shocked by the plight of famine refugees, reworked Muniang into Put Down Your Whip. In his version, a street-performing girl falters during her act and is whipped by her father, drawing the anger of onlookers. A young man shouts, “Put down your whip!” and fights with the father. But the girl intercedes, revealing that the old man is her father, and that their misfortune—wandering homeless, reduced to begging—was caused by war, banditry, and heavy taxes. On October 10, 1931, the play was performed at a cultural event in Shanghai’s Nanhui County. As Japanese aggression intensified and anti-Japanese sentiment soared, Chen revised the play again: the father and daughter became refugees from the Northeast, and the girl’s mother was killed by Japanese invaders. With this change, the play directly targeted Japanese imperialism and became a potent weapon of resistance propaganda.

Statistics show that during the war, Put Down Your Whip accounted for more than 70 percent of all street and rural performances. Prominent actors of the time—Cui Wei, Chen Bo’er, Jin Shan, Wang Ying, Zhang Ruifang, Wang Weiyi, Ling Zifeng, Zhao Dan, and others—took turns performing it. On the street, with no barriers between stage and audience, the play unleashed immense emotional power. At its climax, both actors and spectators shouted together: “Down with Japanese imperialism!” “Drive them out of our homeland!” Many in the crowd tossed coins and bills onto the stage to support “Xiangjie,” the girl.

In April 1937, a performance by Cui Wei and Zhang Ruifang stirred Beijing students deeply. The event, organized by the city’s underground Communist Party, rallied around the newly formed Vanguard of the Chinese National Liberation. More than 2,500 students marched together at Xiangshan. Zhang later recalled how they improvised costumes from local farmers: Cui as the old street performer in a worn cotton robe, rope belt, brimless felt cap, and newspaper visor; she as Xiangjie in a borrowed short jacket and patterned trousers. They even rented a peddler’s carrying pole to complete the scene. Their heartfelt performance against national subjugation electrified the audience. Only halfway through did the police and soldiers realize it was anti-Japanese propaganda—but instead of intervening, they too were moved. One police captain even bought the actors sodas afterward, saying with emotion, “My family is also from the Northeast. I too refuse to be a slave to a lost country.”

During the war, Put Down Your Whip inspired countless stories. In 1937, the Shanghai Women and Children Frontline Relief Troupe braved the bitter cold to perform it for Fu Zuoyi’s troops, who had just repelled Japanese attacks at Bailingmiao in Suiyuan. After the show, the soldiers shouted in unison: “Drive them back home!” In January 1938, the Shanghai National Salvation Drama Troupe performed in Liucun, Shanxi. When the “father” raised his whip on stage, a real old man in the audience—himself a refugee from the Northeast whose son had been an officer in the Northeast Army—suddenly rushed forward with a shovel to strike the actor. Only quick restraint by others prevented injury. The play had stirred too deeply his own grief.

Put Down Your Whip became the signature piece of many actors, with some performing it more than 2,000 times. Between December 1937 and April 1939, the Shanghai National Salvation Drama Troupe No. 2 staged it hundreds of times across central and southern China. It even traveled overseas, to Southeast Asia and the United States, where it was warmly embraced by overseas Chinese. In 1943, Wang Ying performed it at the White House, earning overwhelming praise from American audiences. The play thus brought global recognition to China’s wartime art. Beyond professional troupes, student groups at Zhejiang University, Southwest Associated University, and elsewhere also performed it. Notably, for many later-renowned writers and artists, Put Down Your Whip marked their very first stage role. Writer Wang Dingjun recalled that the war brought him “many firsts”—including his first time acting, in this play. After the July 7th Incident, writer Nie Hualing, then a middle schooler, also joined anti-Japanese propaganda and performed Put Down Your Whip.

During the War of Resistance, Put Down Your Whip stirred enormous public response, awakening national consciousness and inspiring countless patriots. Today, looking back at this classic wartime drama—this “moving torch of resistance”—we cannot help but be once again moved by the powerful national spirit it embodies.

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享