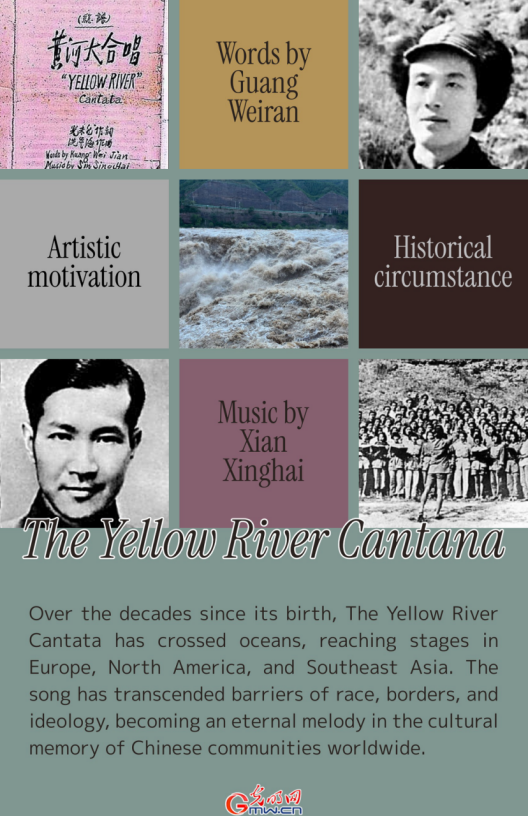

On Chinese New Year’s Eve of 1939, the air in northern Shaanxi was bitterly cold. Yet at the internal gathering of the Anti-Enemy Drama Troupe No. 3, the atmosphere was ablaze with warmth. Twenty-five-year-old poet Guang Weiran recited his newly composed long poem The Yellow River. As the applause subsided, Xian Xinghai, who had been invited to the event, suddenly rose, seized the lyrics in his hands and declared: “I am confident I can set this to music.” The hall erupted in even greater applause and cheers: “A perfect union of poetry and music!”

From March 26 to March 31—just six days—Xian completed composing of The Yellow River Cantata. Those six days, recorded in his diary, became forever etched in the history of Chinese music.

In this large-scale choral symphony of eight movements, Xian Xinghai and Guang Weiran used the struggles of Yellow River boatmen against surging waves as a metaphor, giving full expression to the defiant “roar” of the Chinese nation.

The waters of the Yellow River may come down from the sky, but great music does not fall from heaven. Before this, Xian Xinghai had studied composition at the Paris Conservatory of Music. He was also deeply influenced by the proletarian revolutionary movement, and particularly by the culture of mass singing. After the outbreak of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Xian traveled tirelessly between Wuhan and Yan’an, collecting folk songs, teaching, composing, and performing at the frontlines. Under extremely harsh conditions, he created many powerful vocal works, including Song of the National Salvation Army, On the Taihang Mountains, Guerrilla Army, and Go Behind Enemy Lines. All this prepared the musical language and emotional ground for the birth of The Yellow River Cantata. Its creation was also the result of the profound alignment between artistic motivation and historical circumstance.

In late autumn 1938, Guang Weiran traveled with the troupe from Shaanxi to the Lüliang base in Shanxi, crossing the Yellow River on the way. There, they witnessed the magnificent torrents of Hukou Waterfall and felt the powerful rhythms of the boatmen’s chants. This experience ignited the first spark of inspiration. Early the following year, on his way back to Yan’an after crossing the river again, Guang reunited with Xian—and the spark burst into flame.

While adapting folk songs, Xian Xinghai also pondered the narrative logic of musical structure. To faithfully capture the cries of the Yellow River boatmen, he transcribed the melodic patterns of their chants. These folk motifs were skillfully woven into the choral and orchestral passages, giving the work both the logical development of a Western symphonic suite and the melodic flavor of traditional Chinese tunes. In blending these musical styles, Xian achieved a groundbreaking innovation—successfully fusing Chinese folk elements with Western symphonic form, creating a milestone in modern Chinese music history.

On the evening of April 13, 1939, The Yellow River Cantata was performed for the first time at the Yan’an Northern Shaanxi Public School auditorium. The hall was so crowded that audiences filled the corridors, windowsills, and even both sides of the podium. Everyone came to hear the cry: “Defend the Yellow River, defend North China, defend all of China!” The conductor was Wu Xiling, and the soloists, narrators, chorus, and orchestra were all hastily assembled from students of the Lu Xun Academy of Arts and members of the troupe. Despite rushed rehearsals and simple costumes, the effect was extraordinary. The hall was filled with thunderous applause. Ode to the Yellow River, Dialogue by the River, Defend the Yellow River, Roar, Yellow River—each movement was like a sword cleaving through the heavy clouds of war.

On May 11, at a gala marking the first anniversary of the Yan’an Lu Xun Academy of Arts, Xian Xinghai personally conducted The Yellow River Cantata. Mao Zedong, who watched the performance, praised it highly. Later, after returning from Chongqing to Yan’an and watching the performance, Zhou Enlai inscribed on July 8: “Let this be the roar of resistance, the voice of the people!” With their fiery passion and raw, unpolished performance, the soldiers and civilians of Yan’an carried out a great act of spiritual mobilization. The Yellow River Cantata thus became a “battle trumpet” for the people’s resistance.

In the following months, performances of The Yellow River Cantata quickly spread across the anti-Japanese base areas. Propaganda troupes, schools, and mass organizations all rehearsed and staged it. Because sheet music was difficult to reproduce, many sections were passed down simply “by word of mouth.” Ode to the Yellow River stirred the blood of youth, while Lament of the Yellow River moved mothers to tears. Defend the Yellow River became a rallying cry, emblazoned on anti-Japanese slogans and staged in street theaters. The cantata was not only performed in the liberated areas but also widely sung in the Kuomintang-controlled regions, embodying the unity of the national united front against Japanese aggression. Increasing numbers of soldiers marched into battle singing: “Among the endless mountains, countless anti-Japanese heroes arise! In the green fields, guerrilla fighters show their valor!”

American journalist Edgar Snow, after watching The Yellow River Cantata, remarked: “I first heard Xian Xinghai’s works in Yan’an. Now this young composer’s music and choral pieces are being performed everywhere, from the Yellow River to the Yellow Sea.” He also told Mao Zedong, “This is the finest choral work I have heard in China.”

In 1940, Xian Xinghai traveled to the Soviet Union, where he undertook a comprehensive revision of The Yellow River Cantata. Drawing on performance feedback from the Yan’an years, he reworked many sections originally intended for mass singing into symphonic and dramatic adaptations, making the piece more suitable for large-scale stage performance. He even personally conducted trial performances with orchestras, winning praise in Moscow’s music circles. This version not only preserved the original spirit but also enhanced its expressive power for international audiences.

In 1944, American journalist Israel Epstein visited Yan’an and collaborated with Ye Junjian to translate the lyrics of The Yellow River Cantata into English. Thus, the work made its way onto the world stage, becoming a prominent anthem of the global anti-fascist struggle. On October 24, 1945, at the celebration of the founding of the United Nations, American singer Paul Robeson performed Ode to the Yellow River in English.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, The Yellow River Cantata was performed on many major national occasions. In the 1950s, the “Shanghai Symphony Orchestra version” conducted by Li Huanzhi, and in the 1960s, the “Central Orchestra version” reorganized by the Central Orchestra, both made adjustments to orchestration, harmonies, and instrumentation details. These refinements enabled the work to enter the conservatory system, grace national stages, and be included in music curricula—becoming one of the most representative choral works in the musical history of New China.

After the victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, The Yellow River Cantata was performed in Taiwan. Its first public performance took place in 1947 at Zhongshan Hall in Taipei. More than 40 years later, in 1989, the work was performed again in Taiwan, where its majestic melodies stirred great excitement.

Over the decades since its birth, The Yellow River Cantata has crossed oceans, reaching stages in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. Overseas Chinese communities worldwide have performed it as a symbol of the “soul of the Chinese nation.” As conductor Yan Liangkun observed: “The Yellow River Cantata has had a profound impact among overseas Chinese. Under its immense artistic appeal, compatriots from different regions are united by a shared national sentiment.” In Singapore and Malaysia, Chinese schools and associations have made it a permanent piece in their choir repertoires. At Yangzheng Primary School in Singapore, where Xian Xinghai once taught music, the melody of Ode to the Yellow River still echoes through the old schoolhouse. The song has transcended barriers of race, borders, and ideology, becoming an eternal melody in the cultural memory of Chinese communities worldwide.

More than 80 years later, the melodies of The Yellow River Cantata still resound. It is no longer just a score and a few verses, but a spiritual portrait of generations of Chinese people standing unyieldingly in the face of suffering.

Today, when we listen quietly in concert halls or view the yellowing manuscripts in memorial halls, what we hear and see are not mere echoes and shadows of the past, but proof that the Yellow River still roars. If the Yellow River is the surging lifeblood of the Chinese nation, then The Yellow River Cantata is its immortal hymn of spirit.

By Yu Yafei, Associate Professor, Department of Musicology, Xinghai Conservatory of Music

Guangming Daily, July 29, 2025, Page 1

Translated by Zhang Andi

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享