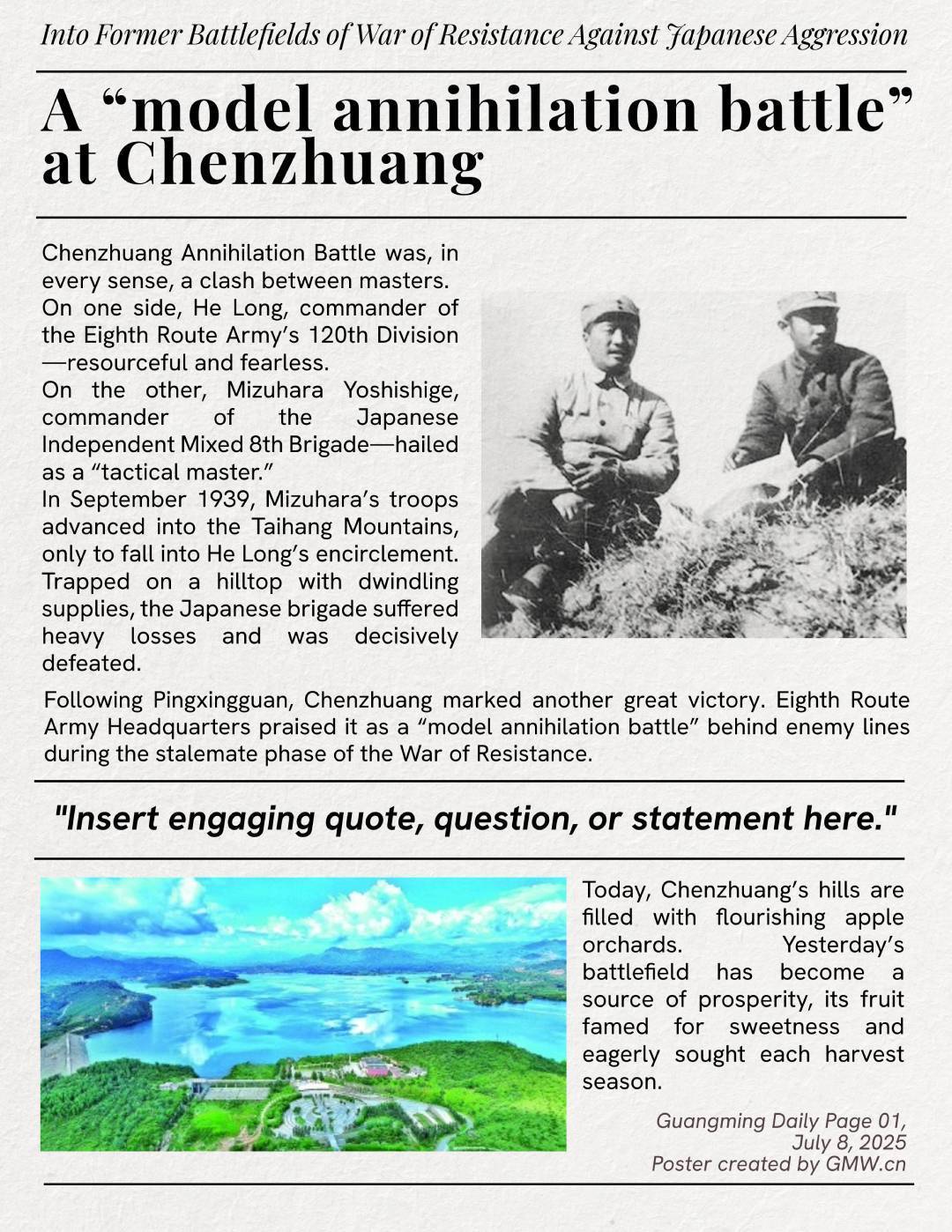

On our side stood He Long, commander of the Eighth Route Army’s 120th Division; on the enemy side, Mizuhara Yoshishige, brigade commander of the Independent Mixed 8th Brigade under the Japanese North China Area Army.

The site: Chenzhuang, Lingshou County, Hebei Province.

As is well known, He Long was among the founders and principal leaders of our forces—resourceful and courageous, a commander who rose from the humblest beginnings and proved unstoppable on the battlefield.

Mizuhara Yoshishige was hailed by the Japanese as a “tactical master.” A graduate of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, he joined the invasion of China after the “September 18 Incident”, noted for cunning stratagems and frequent lightning raids.

Deep in the Taihang Mountains and encircled by rugged peaks, Chenzhuang was a celebrated “model village” during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. It housed the Shanxi–Chahar–Hebei Border Region Government, the Public Security Headquarters, the 2nd Branch of the Counter-Japanese Military and Political University, and several mass national-salvation organizations—earning Chenzhuang the nickname “Little Yan’an.”

A model village like Chenzhuang naturally became a thorn in the occupiers’ side. Yet time and again, their surprise raids were repelled.

On the eve of Mid-Autumn in 1939, after careful planning, Mizuhara set out to seize Chenzhuang in one stroke with 1,500 picked troops.

China’s underground network quickly obtained the intelligence and reported it to the 120th Division. He Long made a snap decision: “Good. We will launch a battle of annihilation and decisively defeat this enemy force.”

The division’s main force then made a forced march of more than 180 li (about 90 kilometers) in a single day and night to reach Chenzhuang.

There were several routes from Lingshou to Chenzhuang. He Long judged that, given Mizuhara’s ambitions, the Japanese troops would bring heavy weapons—and with heavy weapons they could only take the main road outside Ciyu Town. He therefore positioned the main force in ambush on the ridges flanking the road, creating a pocket to trap the enemy.

To lure the Japanese troops deeper, only two Chinese companies were sent forward to make initial contact. On September 25, Japanese forces advanced north from Lingshou toward Ciyu Town with great fanfare, bombarding the lines with artillery and grenade launchers. The Chinese troops feigned weakness and carried out a fighting withdrawal.

Just as the Japanese forces were about to enter the “pocket,” they suddenly halted more than 40 li (around 20 kilometers) from Chenzhuang. Hours went by without any further movement.

By the afternoon of the 26th, instead of pushing forward, they began to fall back toward Lingshou.

Had they discovered our plan? After personally inspecting the front, He Long issued a firm order: proceed exactly as planned.

Such is war: a contest not only of command skill, but of patience and steadiness. Sure enough, at dawn on September 27, the Japanese troops wheeled about and, traveling light, dashed toward Chenzhuang along the southern foothills of Mount Lubai.

He Long ordered again: do not block them—let them get into Chenzhuang. Having pushed in alone, they will not stay long. When they retreat, seize the moment and annihilate them.

The Japanese finally occupied Chenzhuang. Colonel Tanaka Shōzaburō, commander of the 31st Regiment, once wrote in his diary: “To take Chenzhuang without a major battle—that is a mark of command genius…”

Yet the crafty Mizuhara could not bring himself to rejoice.

In Chenzhuang not a soul was to be seen, nor a single grain of food. What “welcomed” them were bold slogans splashed across the streets: “Down with Japanese imperialism!” “Drive the invaders out of China!”

Sensing the abnormality, Mizuhara ordered his men to hastily fortify their positions.

As anticipated, the Chinese forces launched their attack after nightfall. Unfamiliar with the terrain, the Japanese troops huddled behind hastily built fortifications and fired blindly.

At dawn on the 28th, Mizuhara ordered a breakout. Anticipating an ambush along their approach route, he tried a decoy maneuver—pulling his troops back in the opposite direction.

Zhang Zongxun, commander of the 358th Brigade of the 120th Division, reported to He Long. “Mizuhara is up to his tricks again,” He said calmly. “I stand by our assessment—the enemy will double back. Order all units in ambush to be ready.”

An hour later came another report: “The enemy has turned back. Using reeds along the river as cover, they’re skirting the southern bank of the Cihe River at the foot of Mount Lubai, fleeing toward the southeast highway.”

He Long issued strict orders: no one fires without command—wait until the enemy is fully inside the pocket, then strike.

The battle erupted in an instant. From the heights on both sides of the road, the Chinese troops lying in ambush opened fire, cutting down enemy ranks in succession. Within a short time, more than half of the Japanese force had become casualties.

Wily Mizuhara quickly regained his composure and judged the greatest threat to be a spur south of the road—Diegu Cliff. He immediately massed two companies for a strong assault.

The Japanese mounted four assaults in succession, three of which reached the very forward edge of our positions. Eighth Route Army soldiers leapt from the trenches and fought hand-to-hand, forcing the attackers back by sheer resolve.

Failing to break through, Mizuhara shifted the axis of retreat, concentrating his remaining troops to ford the Cihe River and escape to the north.

From a mountaintop vantage point, He Long observed the enemy through his binoculars. He instructed his troops to hold fire until the Japanese entered the riverbank mudflats, then concentrate their firepower for maximum effect.

As they stepped into the mud, the Japanese soldiers became exposed targets.

Only then did Mizuhara fully realize he had met a true master.

The Japanese troops made a last, desperate effort. On September 29, Japanese aircraft arrived to provide cover. Abandoning baggage and heavy weapons, the remnants broke in disorder toward Mount Lubai.

They did not realize they had entered the vast sea of people’s war. The encirclement tightened steadily, while beyond it armed work teams, militia, and local villagers guarded every ravine and path.

Mizuhara was trapped on a hilltop scarcely 250 m in diameter. Deprived of his usual arrogance, he radioed headquarters repeatedly for assistance. Captured Japanese communications later contained the plea: “Request immediate air delivery of ammunition and provisions, and dispatch additional punitive units.”

Most of the airdropped ammunition and biscuits fell into the positions of the Chinese forces, and an 800-strong “punitive detachment” was intercepted well outside the battlefield.

At 7:30 p.m. on the 30th, Chinese troops launched a general assault. Mizuhara was killed amid the rocks by grenades thrown by our soldiers. Thus ended the “Chenzhuang Annihilation Battle” after six days and five nights—over 1,200 Japanese troops were eliminated, and three mountain guns and 23 light and heavy machine guns were captured, among other materiels.

The Battle of Chenzhuang was another major victory after the triumph at Pingxingguan. Eighth Route Army Headquarters praised it as a “model annihilation battle” behind enemy lines during the stalemate phase of the War of Resistance. The National Government sent a telegram to He Long, stating that the victory “boosted military prestige in Hebei and Shanxi and set a model for the resistance in North China.”

Eighty-six summers later, the “Into Former Battlefields” reporting team arrived in Chenzhuang.

Standing beside the Chenzhuang Annihilation Battle Exhibition Hall, Yin Yuguo, Party Secretary of Chenzhuang Town, told reporters: “I grew up with the stories of this battle. Our army won a complete victory, and the villagers contributed by carrying ammunition and stretchers. Commander He Long praised them, saying, ‘Meritorious, meritorious—the people of Lingshou made great contributions to front-line support.’”

Yin explained that Chenzhuang was a model during the war, and after the founding of New China its people remained at the forefront through every stage of development.

Pointing to the apple orchards heavy with fruit on the hillside, he said, “Yesterday’s battlefield is today a treasure trove for people’s prosperity. Look how these trees thrive! Traders say the fruit here is especially sweet. Every year the apples are booked before they even come off the branch.”

“Not just the economy—Party-building and “beautiful-countryside” initiatives—we’re a model in the city. We carry a red revolutionary heritage. Before I even started school, I learned the school song of the 2nd Branch of the Anti-Japanese University.”

We asked him to sing a few lines.

Yin obliged without hesitation, singing: “Our motherland bleeds; rivers and mountains lie in ruins—how can we live without expelling the invaders? We are the new Great Wall of the nation, to stand like the mighty Taihang peaks. We learn in battle, go deep among the people, and carry forward the Eighth Route Army’s glorious tradition. Comrades, uphold the leadership of the Communist Party, drive out the invaders, build a new society—we shall forever be the vanguard!”

By Lei Ke, Geng Jiankuo, and Chen Yuanqiu, reporters of Guangming Daily.

Guangming Daily, July 8, 2025, Page 1.

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享